Why Pussy Riot speaks to the world

In case you’ve been away, here’s a recap: three members of the Russian punk feminist group Pussy Riot, Yekaterina Samutsevich, Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, were arrested earlier this year on charges of “hooliganism driven by religious hatred”, and on Friday they were sentenced to two years in prison for their crimes. The world has spoken out, in a largely appalled and angry tone, against the treatment of these artists, their crime being the performance of a non-violent punk protest song inside a Russian Orthodox church in Moscow.

There is, however, a glaring contradiction in the feel-good uprising aspect of this story, which has seen the world come together in support of these persecuted artists. It remains a hushed, astounding paradox at the centre of the Pussy Riot media maelstrom, seemingly going against the ethos of the whole balaclava-wearing, placard-waving spirit of the matter. That is, Russia, as a whole, is not particularly in favour of the trio, with opinion polls revealing that citizens felt that the band members deserved to be punished, and Russian musicians, in a particularly noteworthy absence, failing to offer any words or actions of support to their contemporaries.

One explanation that has been offered for this eerie silence is the idea that in Russia, Pussy Riot are not actually considered to be contemporaries by professional musicians. And sure, the world has seen no evidence of the musical talents of Samutsevich, Alyokhina and Tolokonnikova other than the thrashing, dubbed-over performance which resulted in their arrest. While all that energetic, brightly-clad leaping is a great spectacle, it says little about the women’s ability to pull off a live gig.

Russia’s history of protest music is known for being much more subdued and accessible, keeping its subversions simmering under works of musical creation so great that even presidents couldn’t bring themselves to prosecute the artists. In the early 1960s, those who composed music outside of the Soviet establishment were “bards”, and their output was dubbed “author’s song” – a name that, in itself, is powerful in its suggestion of individuality and ownership, tying the musician to his music over all else.

This is where Pussy Riot take an impassioned jump out of familiar territory and into an all-new, neon-coloured version of events. With a style that’s more reminiscent of riot grrrl than Russia’s revered Vladimir Vysotsky, the women have alienated themselves from their cultural heritage while simultaneously extending a knowing smirk to the rest of the world, taking on the signifiers and the tropes of a movement much bigger than just themselves.

Riot grrrl bands began appearing in the 1990s in response to an absence, in recognition of things that were going unsaid. A few decades later, Pussy Riot was born of the same impulse; an anonymous member told Vice a while back, “We realized that this country needs a militant, punk-feminist street band that will rip through Moscow’s streets and squares, mobilize public energy against the evil crooks of the Putinist junta and enrich the Russian cultural and political opposition with themes that are important to us: gender and LGBT rights, problems of masculine conformity, absence of a daring political message on the musical and art scenes, and the domination of males in all areas of public discourse.”

The spirit of riot grrrl punk and third wave feminism is alive and well in Russia, then – at least, to its creators. The general oppression of such movements in Russia’s past means that many have been left feeling unmoved by Pussy Riot’s display. Meanwhile, in the rest of the world, this stuff is all clearly still fresh and important to us, as the global response to Friday’s verdict has brilliantly revealed. Punk is not dead, after all.

According to Maria Klassen, a “Russia expert” quoted in this article from Deutsche Welle, Vysotsky and his contemporary Bulat Okudzhava both drew their popularity from their broad appeal, something which apparently Pussy Riot have failed to achieve in Russia as a whole. “Back then, those types of bards weren’t only known by the intellectual crowd, but also by the general population,” Klassen clarifies. “They were appreciated for their insightful language and their ability to talk to anyone. That’s how they became the megaphone of many.”

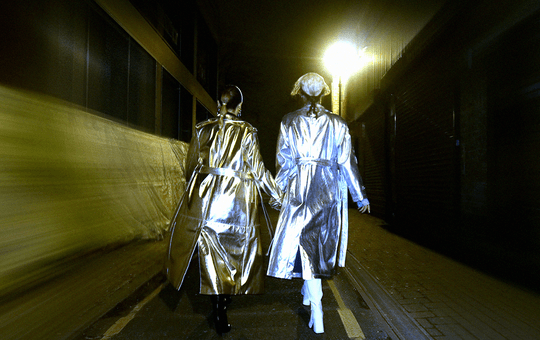

Speaking a language that’s new to Russia – specifically, a language of colourful costumes, rowdy guitars and anger-mangled melodies – this fresh wave of punk feminists are reviving something that’s familiar and perhaps nostalgic for us outsiders, but a brave and even alienating choice for a Russian audience. What it means, though, is that while the trio have been imprisoned and their characters defamed in their home country, they have become icons across the rest of the punk-recognising world, who have sat up and started paying attention to the fact that Russia is actually quite a dodgy place to live if you have opinions.

Still, the Pussy Rioters can be said to have kept alive something of the spirit of the bards that went before them; as Vladmir Vysotsky is quoted as having said, “author’s song demands great work. This song is always living with you, never giving you rest.” As Yekaterina Samutsevich, Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova begin their two year sentence in jail, and as protestors organise wildly inventive demonstrations and shows across the world demanding their release, one thing cannot be disputed; the spirit of Pussy Riot’s song is alive, and the artists, and those who appreciate their music and their right to make it, are living it.

To show your support for Pussy Riot, contact either “Amnesty International”: or your local Russian Embassy. Or maybe start a punk protest group of your own.