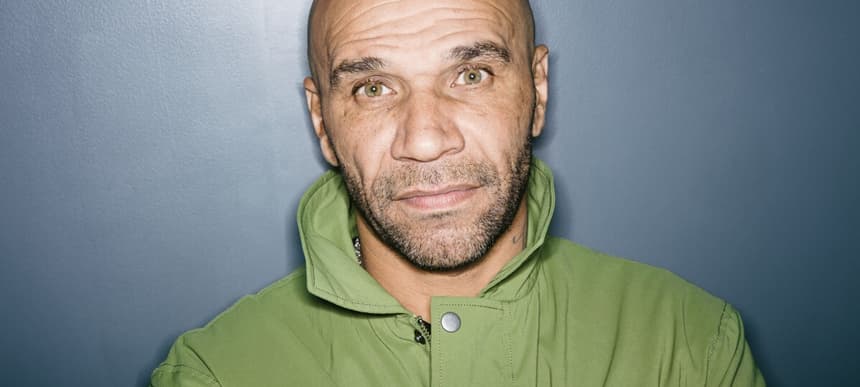

Goldie: A Man At War With Time

“Aren’t you both ying and yang? When you go to work, do you think both good things and bad things in the space of five minutes? Yes, you do. If you don’t, you’re a lying fuck.” That’s Goldie talking. “It’s called being human.”

Fifty-one, living in Thailand, and seven years into a love affair with yoga, he talks in aphorisms – about change coming from within, and focusing on today to create tomorrow – and beams audibly about his new state of calm.

Today, though, he’s got a bee in his bonnet. “A very fucking big bee,” he says. “When it comes to music, I take it very seriously.”

We’re talking about his new album, The Journey Man, which is his first solo long player in almost twenty years. Twenty years in today’s technology-accelerated society is a long time. iPhones, Uber, Spotify, Facebook, YouTube, Soundcloud: these are all things that twenty years ago were still but a twinkle in their respective creators’ eyes. And that’s a point not lost on Goldie.

“It’s twenty years since Timeless was made,” he says, “and it was around that time that another [proper] album got made.” Like many of the rock stars of that late-nineties generation – think your Gallaghers, your Ian Browns – a bit of hyperbole is rarely lost on Goldie. “I kind of feel like if Timeless had been surpassed, I wouldn’t have done an album,” he goes on. “This is an album, it’s a real long player.”

“A real long player.” You could argue that in today’s playlisted-world the concept of the long player – a term that was once tightly tied up with vinyl culture, but has since come to refer more generally to albums and their opus potential – is something that, along with the CD and tape deck, is slowly fading from relevancy.

And you might find Goldie (begrudgingly) agreeing with you. “I think that the minute that music became downloadable,” he says, “part of the art died right there.”

“I think that the minute that music became downloadable, part of the art died right there.”

It’s a gripe he retreats to frequently, and you get the sense of a man tussling with the world as it turns its ever-minimising attention to the flicker and scroll of a smartphone screen. But he’s not giving in. “You can download it, right? It’s cool, I get it. But you can’t compromise fucking art,” he’s pouncing, “you can’t download a canvas, you have to go and look at it in a gallery. I like that aspect, and The Journey Man for me was how can you fucking deny that it’s a fucking great long player, it’s a great piece of music?”

Split into two parts, the album stretches to sixteen tracks and spans jazz, funk, lovers rock, soul and R&B – and sounds every bit a Goldie album, stuffed with the melodic drum & bass stylings that made the world sit up and listen all those years ago.

It’s quite literally a long player too, clocking in at a shade off two hours. “People go, ‘why did you make it so long?’ and I’m like ‘er, Spotify? Have you heard of it? You can press fast forward on it when you want,’” he assails, seething sarcastically, “fucking moaning at me asking why it’s too long for…”

-7.jpeg)

As with so much of what Goldie has to say, behind the braggadocio here there lies a salient point. In intimating that people are disrespectful of the album format, and will nowadays choose to skip from track to track on whatever digital service they prefer rather than listening through as the artist intends, he hits – intentionally or not – on the fact that musicians are increasingly packing out their albums with more tracks in order to clock up more individual plays (and therefore revenue) on streaming services. When pressed to expand on this point, however, he trails off onto another subject, disinterested in discussing the machinations of the industry.

It’s perhaps in this that you can see the contradictions at the heart of Goldie’s character: he’s powerfully passionate about his art (and he won’t hear it called anything else), and yet increasingly trapped in a world that seeks to undermine it. Talking about his own album, he suggests you could take his name off it and put jazz or funk or soul artists’ names next to the relevant tunes on the record. “That’d make a fantastic Spotify playlist, wouldn’t it?” he says, without so much of a nod to the fact that that was exactly how one of the year’s biggest selling albums has been marketed. To Goldie, it’s just about art – and you can believe it: no one chasing down streaming figures puts an eighteen-minute track on their album.

“The industry – and the machine that it is – that for me, it doesn’t appeal to me,” he says, his verbal discontent at times appearing as a mask for apathy. Admittedly, apathy isn’t a word you’d often find used to describe Goldie – a man who you might wager considers drum & bass to be slow, such is the energy with which he conducts himself outside of the yoga studio – but you get the sense, having breached fifty years, that he’s benefitting now more than ever from perspective.

In the same breath that he describes club culture as “fucked”, he dives into his history: “Were you there when Spectrum closed? Were you there when Heaven closed?” he says. “It’s not anything fucking new that clubs open and close, it’s just that you’ve only really experienced club culture for twenty-five years. Jazz has been around a lot longer than that.” “The weather’s always been around,” he goes on, diving into a characteristically loose analogy, “but now you’ve got your fucking iPhone and an app and you’re all ‘oh no, it’s really bad and the world’s going to end.’ No, the weather’s always been fucked.”

“The weather’s always been around, but now you’ve got your fucking iPhone and an app and you’re all ‘oh no, it’s really bad and the world’s going to end.’ No, the weather’s always been fucked.”

If anything, that’s his real problem with a new, technologised generation: it’s not so much the formats, as the attitudes that appear to come with them. “People are very quick to have all this connection with their iPhone fucking SA7s or whatever they’ve got,” he says, “but they’re so fucking ill-informed and non-connected in terms of the hereditary situation with this music and where it comes from. And I think you should be dutiful to where it comes from, because you might pay it a bit more respect.”

-6.jpg)

If that’s what The Journey Man sets out to achieve then you’d have to say it does a fine job of it – regardless of whether you’re listening on a turntable or on iTunes. It’s deeply connected with the musical influences that run deep throughout Goldie’s back catalogue. And that’s the only real connection he says he’s interested in: “What I play in a club, I’ll play the next fucking day because I stand by the music because I actually love the music,” he says, railing against a new generation of DJs who he says have “sold [their] fucking souls” by toeing a line and playing “manufactured, bullshit music ‘for the kids’.”

“There are some people that aren’t connected to the culture, my friend,” he says, sounding both at once exasperated and phlegmatic. “You can sit around and blame the CD generation for that – fast forward, skip – but culture won’t survive on Spotify. It can’t, can it?”

Ultimately, though, this is not something he’s preoccupied with or even apparently worried about. In fact, despite all of this (or perhaps in spite of it), he’s not a man too interested in what the future might hold. “What am I,” he says, “Mystic fucking Meg? I don’t have a crystal ball, sunshine.” He slips back into aphorisms, about seizing the day, the future existing only as a realisation of a consecutive present, and our responsibility to remember yesterday and today in creating what comes tomorrow. “A truthful idea,” he says, “lasts the honesty of time.”

“What am I, Mystic fucking Meg? I don’t have a crystal ball, sunshine.”

And just like that, we’re back to talking about his yoga practice again. “That’s where the power of the album comes from, really,” he says, and talks about the duality in the album’s title, referring to both the man and the journey – both reflective and reflexive, encompassing everything that’s passed not just in the twenty years since his last long player but all that came before that (and before him) too.

“I think this is an adult album, it could have been called ‘Music for Adults’ or ‘The Proustian Effect’ or,” he’s laughing now, at himself perhaps, “‘Stop Making That Shite, There’s Other Stuff Over Here’.”

In some ways though, given all of this, it’s a shame that the name ‘Timeless’ was already taken.

The Journey Man is out June 16th.

Listen to a playlist of advance tracks from the album below:

Goldie & The Heritage Orchestra Ensemble headline Funk The Format Festival on Saturday 17th June in Hove Park, Brighton.

Read more: The 10 Best Drum And Bass Tracks According To Goldie